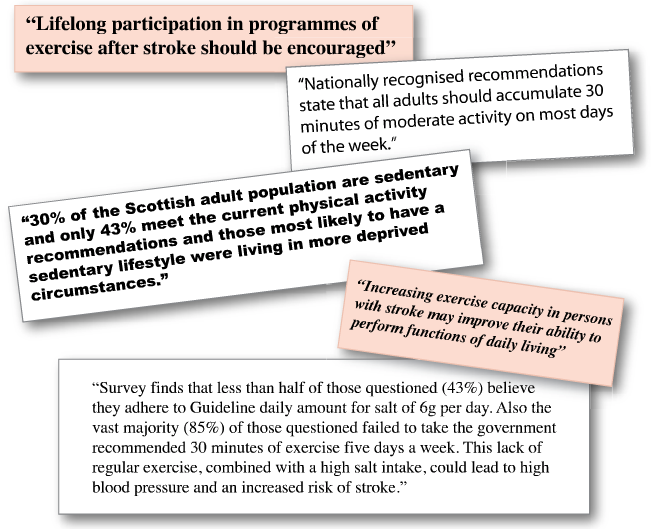

- There is substantial evidence to support the beneficial effect of regular physical activity on risk factors for stroke including hypertension, glucose intolerance, low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations and obesity.

- Physical activity may reduce the risk of stroke (both ischaemic and haemorrhagic) and is an important modifiable risk factor (this evidence was in relation to primary prevention but it is reasonable to extrapolate from this that there will be a secondary prevention effect).

- There is a direct and dose respondent relationship between blood pressure and stroke risk.

- Activity helps to lower BP and improve lipid profiles, improve endothelial function and vasodilation and reduces blood viscosity, fibrinogen levels and platelet aggregability.

- Moderately active people have 20% lower risk of stroke.

- Highly active people have 27% lower risk of stroke.

Category: Advancing Modules

Physical activity

Headlines

Approaches to treatment

- PFO associated with stroke is relatively uncommon so we lack relaible evidence about which treatment are best.

- The risk of recurrent stroke is only about 2% per year – so RCTs need to be very large with long follow up to demonstrate that a treatment has reduced this risk significantly.

- Aspirin (or other antiplatelet drug) – relatively safe and well tolerated.

- Anticoagulation – likely to reduce clots but associated with significant bleeding risk and Warfarin is inconvenient. Young patients face many years of treatment.

- Percutaneous closure of PFO – PFOs can be closed during a cardiac catheter procedure. This procedure carries risks of arhythmias, bleeding and embolism of the closure device.

- Decisions about treatment need to take account of an individual assessment of the patients risks and take account of their beliefs and concerns.

Quiz

Patent foramen ovale

Introduction

- A patent foramen ovale (PFO) is present in all babies prior to birth (to allow blood to by-pass the lungs which are not used in utero) – in 80% of people it closes after birth

- It occurs in about 1 in 5 (20%) healthy individuals.

- It is associated with about a 3 fold (relative risk = 3) risk of stroke in younger adults.

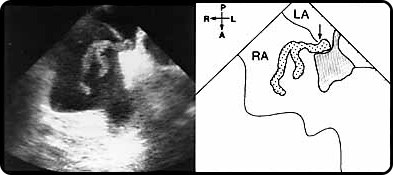

- It may provide a route for so called “paradoxical emboli” to move from clots in the veins to the brain by by-passing the lungs which usually filter out clots. The illustration below shows a large clot going through the PFO.

- It can be detected by a transthoracic or trans-oesophageal echocardiogram with bubble contrast (see video of bubbles crossing septum) or transcranial Doppler.

Duration: 10 seconds

References

- Royal College of Physicians (2016)

- Townend, E., Brady, M., & McLaughlan, K. (2007). A Systematic Evaluation of the Adaptation of Depression Diagnostic Methods for Stroke Survivors Who Have Aphasia. Stroke; 38: 3076 – 3083.

Which of the following actions are appropriate and which are inappropriate when carrying out mood screening?

How can these tools be used with people with aphasia?

- If someone has a communication problem then adaptations can be made to the assessment.

- Adaptive methods included:

- using informants (relatives or staff)

- increased reliance on clinical observation

- modifying questions (simplifying to yes/no answers)

- visual analogue scales.

- See Townend, Brady, & McLaughlan (2007) for a systematic review.

- Smiley faces or observational criteria on their own should not be used diagnostically (RCP, 2016).

- Similar adaptations could be used for those with significant cognitive impairment that is affecting assessment.

- Consideration should also be given to those with visual and visuospatial problems where horizontal (left to right) visual analogue scales may be difficult to interpret.

Mood screening

When should you screen for mood disturbance?

- RCP Guidelines (2016) recommend that all stroke patients should be screened for mood disturbance initially and then at regular intervals particularly before discharge and when active rehabilitation is stopped.

What does a mood screening tool do?

- A number of different standardised mood screening tools exist. The aim of these tools is to screen for the possibility of the presence of a mood disturbance.

- Screening questionnaires are not diagnostic. All of them have limitations meaning sometimes patients’ problems will be missed or overestimated. Screening questionnaires are designed to be used to help decide who to refer for clinical interview and more specialist assessment.

- Assessment of mood disturbance following a stroke in complicated. There is significant overlap between symptoms of depression and anxiety, and common physical and cognitive consequences of a stroke (e.g. reduced concentration, disturbed sleep, increased fatigue, reduced levels of motivation).

- Always consider the reason why someone may give a particular response to a question on a screening or may be displaying a certain behaviour and discuss fully with multi-disciplinary colleagues.

Which mood screening questionnaire should I use?

- There is a lack of consensus both within the research literature and within clinical practice over the best mood screening tool to use. However, RCP (2016) guidelines suggest the use of validated simple measures such as the GHQ-12 or PHQ-9 for screening for depression.

- No recommendation is made for screening for anxiety or emotional lability.

- Many questionnaires are subject to copyright conditions that should be adhered to. Further information on the screening tools used throughout each case study can be found in additional information boxes.

- See local policies for the tools used with your organisation.

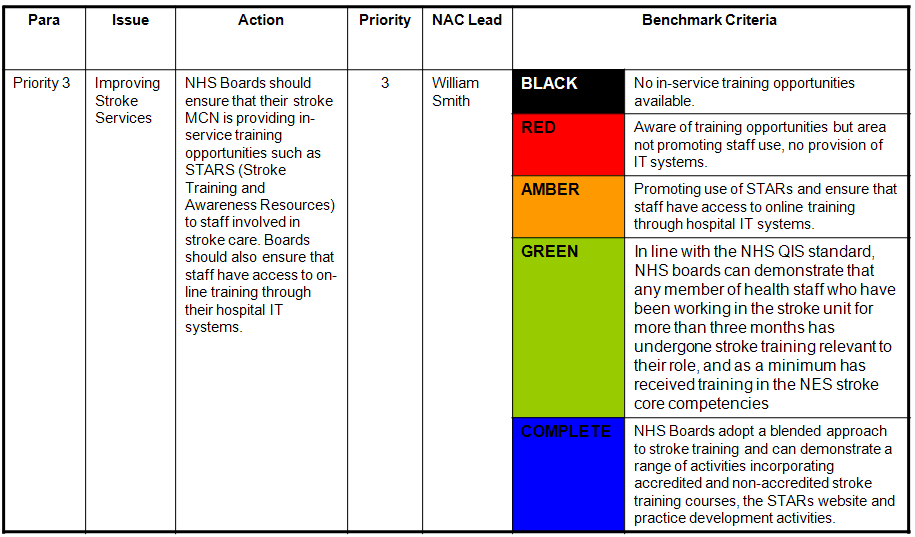

Example Priority (No 3)

Below is an example of one of the current top 10 priorities.

It has a clearly defined ‘Action’, an identified person who is responsible for overseeing the delivery of the action from the National Advisory Committee for Stroke at the Scottish Government and benchmark criteria.

The Action Plan Coordinator reviews performance with MCN Managers at the National MCN Managers Meeting and with clinical teams during official Board visits and the progress is updated accordingly.