- The frequency of depression is around 33% within the first 12 months following a stroke.

- Research has indicated that abnormal mood impedes rehabilitation.

- Depression is associated with increased mortality at 12 months post stroke.

- Diagnosis of depression is a complex task following stroke due to the significant overlap of physical and cognitive consequences of stroke.

- Depression is not an inevitable long term consequence of stroke and much can be done to help those who have a depressive episode.

- Severity of mood disturbance is associated with severity of cognitive and physical impairment and sometimes, but not always, there is a decrease in level of depression as a person gains function.

- There is no conclusive evidence that the onset of depression is associated with one particular type of stroke.

- SIGN 118 (2010) and RCP (2016) recommend that all stroke patients should be screened for mood disturbance.

- SIGN 118

- Royal College of Physicians

Category: Advancing Modules

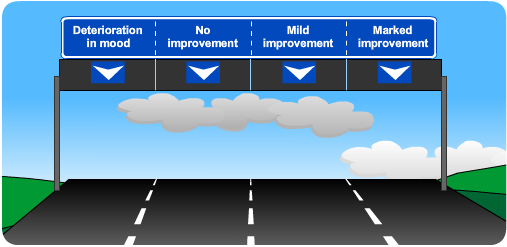

Marked improvement

Mary is keen to engage in treatment sessions and activities and is feeling more positive about her future.

Mary: GHQ-12 (Marked improvement) [PDF, 183KB]

What should the team do?

- Mary is given positive feedback from the team and her family. Her mood is regularly reviewed.

- Mary is encouraged to take more control of her rehabilitation and set her own goals for recovery.

- She is introduced to the concept of self-management (the ability to manage her own symptoms) for her to continue with in the community.

- At the point of discharge planning the team meet with Mary and her family to produce an ‘relapse prevention’ plan to keep Mary active in the community. (click on the PDF link below to see an example of a ‘relapse prevention plan’) Although Mary is no longer depressed she is still potentially vulnerable to further depressive episodes in the future.

- The discharge letter highlights to the GP that Mary has been depressed during her admission although she has progressed well. The stroke nurse specifically asks Mary whether she is depressed or not and how she is feeling at her follow up visits.

Mild improvement

Mary begins to see improvement and becomes more involved in activities within the ward setting.

Mary: GHQ-12 (Mild improvement) [PDF, 183KB]

What should the team do?

- Mary is given positive feedback from the team and her family. Her mood is continually reviewed.

- Mary is encouraged to take more control of her rehabilitation and set her own goals for recovery.

- She is introduced to the concept of self-management (the ability to manage her own symptoms) for her to continue with in the community.

- At the point of discharge planning the team meet with Mary and her family to produce a ‘relapse prevention’ plan to keep Mary active in the community. (click on the PDF link below to see an example of a ‘relapse prevention plan’) Although Mary has made good progress she is still potentially vulnerable to further depressive episodes in the future.

- The discharge letter highlights to the GP and ongoing community rehabilitation services that Mary has been depressed during her admission although she has progressed well. Community rehabilitation services monitor Mary’s mood during their input. The stroke nurse specifically asks Mary whether she is depressed or not and how she is feeling at her follow up visits.

No improvement

Mary continues to be moderately depressed and shows no real change in her mood state.

Mary: GHQ-12 (No improvement) [PDF, 183KB]

What should the team do?

- The team continue to monitor Mary and work on enhancing her self-efficacy (her belief that she can achieve goals and targets).

- She is asked to re-consider trying an anti-depressant medication. She agrees to this in the short term. She finds this has a moderate beneficial effect on her mood and allows her to sleep better and improves her appetite.

- In addition they refer her to clinical neuropsychology services. The clinical neuropsychologist works with the occupational therapist in engaging Mary in a formal problem-solving intervention. Problem-solving deficits are often found in people with depression. In addition Mary also has problem-solving deficits due to her stroke. Mary finds that her improved problem-solving skills help her when she approaches new difficult situations. Her enhanced problem-solving skills reduce her tendency to fail in new situations thereby reducing the frequency of interpreting such failures in a negative and self-critical way.

- The clinical neuropsychologist also offers Mary and her family some time-limited sessions exploring how they are coping with changes in Mary’s skills and abilities. These sessions enhance Mary and her family’s understanding of her situation and the expectations they have about her recovery.

- When Mary is discharged her depression on the ward is highlighted in her discharge letter and her GP is asked to regularly review her medication. The stroke nurse who visits Mary at home also closely monitors her mood and completes further mood screening at regular intervals.

Deterioration in mood

Mary is more tearful and withdrawn. She is refusing to attend therapy sessions including physiotherapy. She is hardly eating any food and is starting to lose weight. Her family are struggling to get her to talk to them when they visit and she expresses negative thoughts about her future. She told her husband that she was a burden and that he would be better off if she were dead. She turned her head away when her named nurse asked her to fill in another GHQ-12.

What should the team do?

- The team refer Mary to liaison psychiatry services for assessment. Mary reluctantly agrees to referral.

- The psychiatrist assesses Mary and finds her to be significantly depressed. He discusses again the pros and cons of anti-depressant medication. Mary again voices concern about medication but after discussion with her husband who is quite distressed she agrees to a trial of medication.

- The psychiatrist keeps Mary’s condition under review and adjusts her medication as necessary. He arranges for a community psychiatric nurse (CPN) follow up when Mary is discharged from hospital.

- Mary is also referred onto clinical neuropsychology services for specialist 1:1 psychotherapy. Mary responds to medication and once her depression is slightly alleviated she engages in therapy. The clinical neuropsychologist meets with Mary on a regular basis. Therapy consists of a combination of allowing Mary the space to talk about her changes in function and cognitive behavioural therapy to focus on the negative thoughts that Mary has about her abilities and recovery that maintain her depression. The CPN and clinical neuropsychologist regularly liaise with each other.

Mary’s outcome

Staff monitor Mary and her progress through discussion, observation, and repeat mood screening (3-4 weeks) after treatment commences.

What happens next?

Who could be involved in helping decrease Mary’s level of depression?

At an initial stage of mild to moderate depression a patient does not necessarily need specialist help from a mental health specialist. Any member of the multi-disciplinary team can help try to increase Mary’s activity level within a clearly defined treatment plan paying appropriate attention to physical, cognitive, and emotional limitations. Using resources such as family members, volunteers, and the Spiritual Care Service (who can offer support and guidance to people who follow a faith and also to those that do not) may be beneficial.

Raising awareness of the patient’s individual needs with all staff who come into contact with them can also be helpful. All staff may be able to offer both practical support and be able to show empathy and understanding towards Mary.

Mary’s treatment choices

Mary and Dr Smith discuss treatment options. Mary is reluctant to take an anti-depressant. She does not like the thought of “taking more pills to make me feel better” and is concerned about possible side effects. The consultant discusses these beliefs with her and informs her that anti-depressants are not addictive, He explains that the MDT will closely monitor for benefits she may feel from taking anti-depressants or for any adverse side-effects. After this discussion Mary still wishes to try to make some improvements without medication.

MDT staff, Mary and her family agree to try to increase Mary’s activities and level of engagement with the aim of increasing her enjoyment and pleasure and therefore possibly reducing her depression. Establishing realistic goals with Mary may also help her treatment. Click on the ‘Additional information’ button below for more information about goal setting.

Recommended treatment

NHS Improvement 2011 guidelines recommend that those diagnosed with significant depression should be offered a course of anti-depressant medication. No recommendations are made about the drug of choice and people should be prescribed medication according to local prescribing protocols and British National Formulary (BNF) recommendations with consideration given to the person’s age and other medications.

Those with mild depression should be offered an opportunity for psychosocial interventions including:

- Increased social interaction

- Increased exercise

- Realistic goal setting

- Information provision

In addition there is increasing evidence for psychological therapies that can be included in standard stroke care having a beneficial effect preventing the development of mood disorder. For example:

- Motivational interviewing

- Motivational Interviewing Early After Acute Stroke (Watkins et al., 2007)

- Problem-solving intervention (Robinson et al., 2008)

- Psychosocial behaviour intervention (Mitchell et al., 2009)

All treatments both pharmacological and non-pharmacological should be monitored for effectiveness and changes made accordingly.